American Dreamers

November 12, 2020

The Oxford dictionary defines the American Dream as “the ideal by which equality is available to any American, allowing the highest aspirations and goals to be achieved.” Sounds nice, right? But it’s also broad, perhaps too broad.

Ask any two people what the American Dream means to them, I guarantee you won’t get the same answer. To truly understand the American Dream, we first need to ask ourselves, who’s the dreamer?

“I consider there not to be the American Dream, but American Dreams, plural,” said Oregon State Colonial History professor Ben Mutschler. “In my classes, I distinguish two classic kinds of dreams, represented by Chesapeake and New England.”

Chesapeake’s dream is the classical idea of the self-made man. “If you think of Thomas Jefferson and Jeffersonian Democracy… the only citizen who can truly be a good democratic citizen is someone who’s economically self-sufficient,” said OSU History professor Marisa Chappell. “That, by definition, was a white male landowner.”

“In [the colonial era], the emblematic figure is Ben Franklin,” said Mutschler. “In a period where people could start to fashion themselves to transcend boundaries of class, Franklin jumps from being a commoner to somebody who achieves gentlemanly status. He not only wants to work hard, he wants people to see him working hard.”

I feel like I’ve seen that in a movie somewhere. Chesapeake’s dream is easily the most popular interpretation of the American Dream, at least in American media.

“The idea was that the United States offers the opportunity for anyone to rise up and gain economic self-sufficiency,” said Chappell. “You have the Horatio Alger novels in the 19th century of ‘rags to riches,’…. [and] you’ve got real-life Alger stories like Henry Ford. That kind of mythology has real power in American society to this day.”

The second dream comes from New England, based on the ideal of a city on a hill.

“There’s a whole other set of dreams out there of America as a utopia,” said Mutschler. “John Winthrop, the first governor of Massachusetts, talked about a community of peril, where we’re bound together through the fact that all of us face God’s dangers. That kind of dream is a communitarian dream.”

Two dreams, one focuses on personal economic success, the other on the welfare of the people. Where have I seen this before? While both of these dreams are noble on paper, neither take into account the elephant in the history book.

Though the Founding Fathers claim “all men are created equal” and are endowed “with certain unalienable rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness,” they were slave owners. One of the first Americans to question this was Frederick Douglass.

“Frederick Douglass has a speech that he gave in the 1840s called ‘What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?’,” said OSU 19th Century History professor Stacey Smith.“He was one of the people who pressed the United States to look at its own sins and to think about the ways the Declaration pushed Americans to live up to those ideals.”

Of course, you can’t talk about civil rights in the 19th century without hearing Abraham Lincoln’s name.

“Lincoln was convinced that the United States’ founding principles were in the Declaration of Independence, and he hated the Dred Scott decision,” said Smith. “His interpretation was that the founders didn’t think all people were created or treated equally, but they realized it was an ideal to strive toward.”

Post Civil War, Chappell mentions Ella Baker as another key figure in the conception of the American Dream.

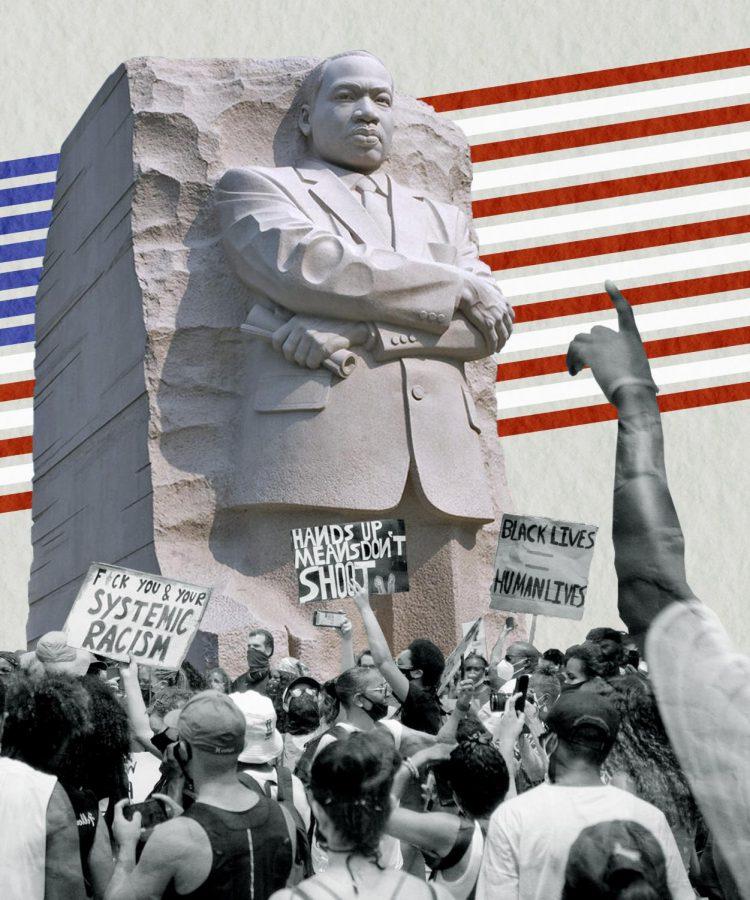

“Baker was a civil rights activist who represented an aspect of the black freedom movement that envisioned the American Dream as a much more egalitarian and collective dream,” said Chappell. “You can think of Martin Luther King Junior’s evocation of the beloved community, that society ought to be more socially oriented.”

In this day and age, we can still see how different dreams drive America.

“In our presidential campaign, you’ve got different models of what the American Dream is and what we ought to do to reach it,” said Chappell. “You’ve got Donald Trump and a republicanism that’s increasingly emphasizing ethnic or racial nationalism, reserving the American Dream for particular groups of people…

“You’ve got people, like Bernie Sanders, on the other side, with supporters who are saying we need social rights, social citizenship, we need as a society to come together and make sure people have access to free education and healthcare.”

At its core, the American Dream is nothing except a standard for the current age of dreamers to hold themselves to. It’s not perfect, far from it, but it’s closer now than it was in 1776, and as time passes we can hope to keep getting closer to that vision of utopia.

We just need to keep dreaming.