Editor’s Note: This is an opinion piece and does not represent the opinion of Beaver’s Digest. This op-ed reflects the personal opinions of the writer.

Picture this: You and your mom get into an argument. You immediately google the definition of gaslighting and find out it is a symptom of a narcissistic personality disorder. Maybe your mom is undiagnosed. You start researching more symptoms.

I won’t tell you whether she actually was gaslighting you or not. And I won’t tell you I would do anything differently. But as a psychology major, I have some thoughts.

Perhaps the next time you get the urge to diagnose yourself or others with attention-deficit activity disorder or something else using websites like Heathline.com or Psychology Today, you can do me a favor and ask yourself: “How is this diagnosis going to help? Am I going to use this false diagnosis to harshly judge myself or others? Am I going to actually seek appropriate treatment and look for a therapist, or use these symptoms as an excuse?”

While I’m thrilled that my generation, Generation Z, is open and honest about the state of our mental health, studying psychology has helped me understand that the way we talk about mental health isn’t always helpful. As always, it’s especially bad on social media.

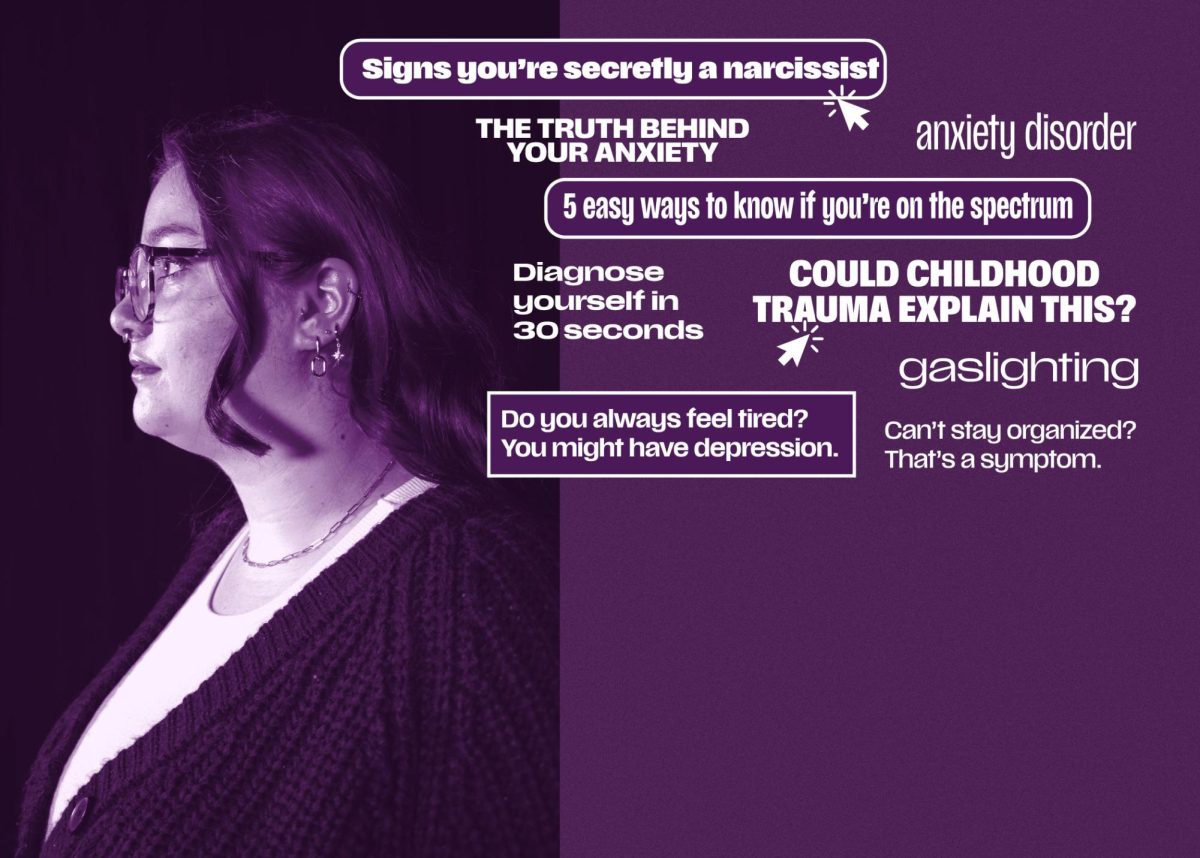

There has definitely been a rise in mental health discussion on social media platforms, with many content creators opening up about their own personal stories. This online discourse can be helpful to start conversations and raise awareness, but the fast pace of social media and the rapid content production can lead to the spread of incomplete or inaccurate information — and often does.

The social media company Meta recently announced they are removing fact-checking features off their platforms. Now, more than ever, we need to be even more vigilant about believing what we see on these platforms.

Even with regulations, social media content can still send the wrong message about psychological conditions. It can bypass the load-bearing skepticism of the scientific method that psychology relies on and spread myths that integrate into our understanding of the human mind.

Kearney Smith, who recently graduated from Oregon State University with a psychology degree, said they are concerned about online conversations on mental health, especially due to the lack of regulations and fact-checking.

“I cannot tell you how many times I’ve scrolled (on) TikTok and I’ve seen something pop up where it’s like, ‘Are you not able to focus?’ or ‘Do you do this one little thing? (That means) you’ve got autism,’” Smith said.

Smith, who has been diagnosed with ADHD, said they experience symptoms of autism spectrum disorder and added that this type of content can be harmful and even make people with autism feel left out or invalidated.

Social media content can, at times, come across as absolute. When creators share personal stories of their mental health challenges, it appeals to our ethos so much that we can’t help but accept them as reality. But psychological symptoms and conditions look different in everyone.

“In the realm of psychology, different kinds of therapy work for different kinds of people,” said Kennedy Klumker, a fourth-year psychology major at OSU.

The people who diagnose and dispense these therapies have doctorates, though. They have the background training that helps them understand the nuances that simply cannot be translated in a 15-second clip or 800-word article.

“In Gen Z, people tend to self-diagnose based on information they see on the internet, or misunderstand the results of scientific studies, specifically psychology studies,” Klumker said.

Sometimes, it’s not even helpful for someone to receive a diagnosis. A 2024 study found that individuals faced greater stigmatization after getting diagnosed by a mental health professional, which had greater negative consequences on their emotional wellbeing.

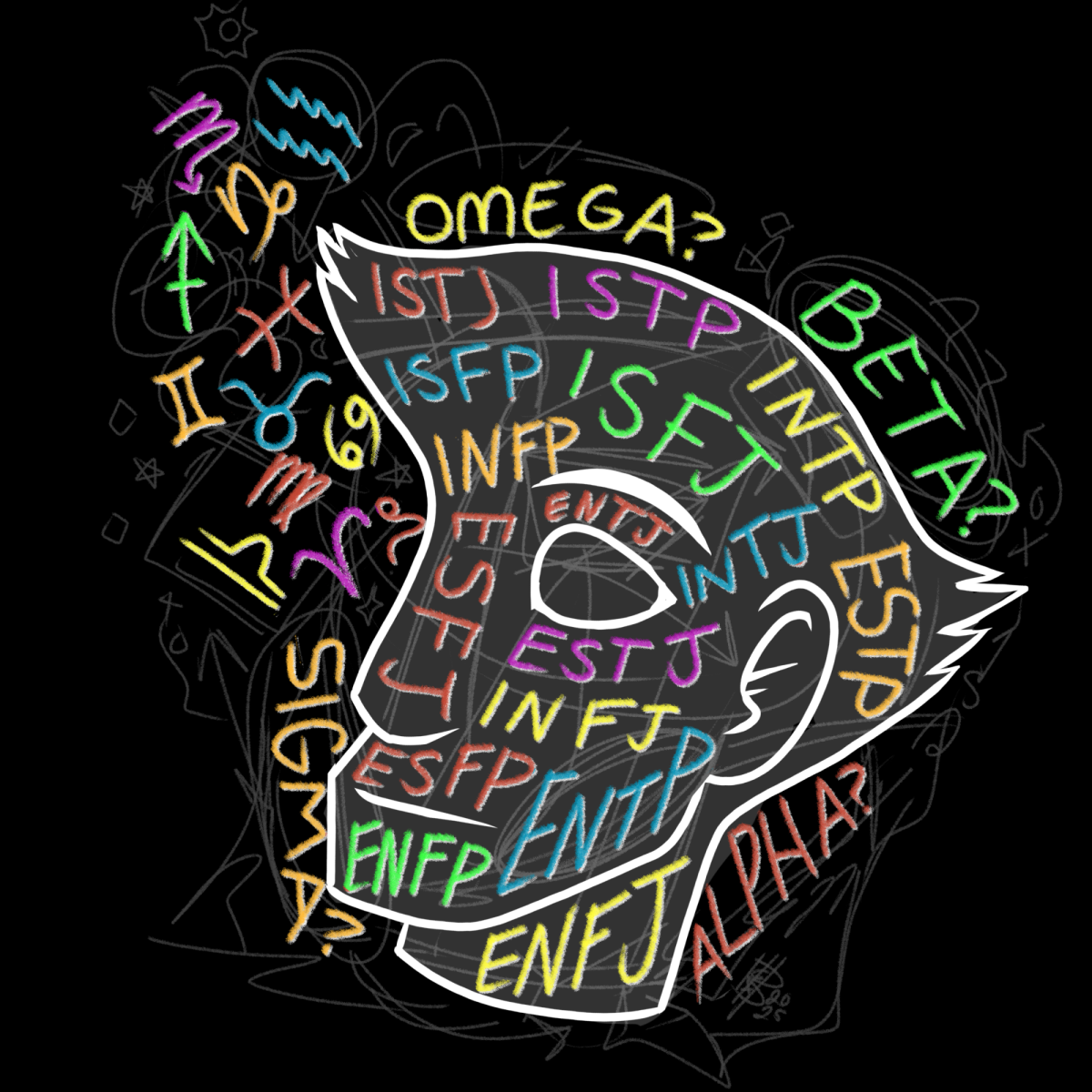

But we want to label and categorize everything and everyone. It’s human nature. So when it comes to understanding how our minds work, a question for which we still do not have a concrete answer, it makes sense that we want to label and categorize our behavior.

I have noticed that the mental health terms often used on social media — like narcissistic personality disorder or generalized anxiety disorder — are actually derived from definitions and criteria written in the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,” aka the “DSM-5.”

But don’t be fooled — the “DSM-5” has flaws.

It is the best reference psychologists have to help diagnose, but it is constantly under review and critique. The most important critique, in my opinion, is that it probes the human mind from a primarily-Western perspective.

The field of psychology isn’t that diverse to begin with. In 2023, almost 70% of members of the American Psychological Association identified themselves as “white” or “European American.” Psychology still lacks a thorough understanding of cultural backgrounds and non-white identities.

We are still finding ways to serve people from all different backgrounds and identities. It’s important to remember that psychology is a collection of theories, developed on years of research that have been conducted primarily by white researchers, some of which has been done unethically and with racial and gender biases.

“Psychology is still a very young field, and we don’t really know everything about what we’re doing,” said Haley Reid, a fourth-year psychology major at OSU.

After all, it wasn’t that long ago that Sigmund Freud — the daddy of psychodynamic theory — was defending the use of cocaine for psychological purposes and even prescribing it to his friend.

My point is, there is still a lot we don’t know about psychology but what we do know is still more accurate than what’s on social media. It’s peer-reviewed. It’s done by professionals.

Smith advised others to question everything they come across, especially on the internet, with a healthy level of skepticism.

“Doing your research … I think it pays off, not only for you, but for other people,” Smith said.

It’s an imperfect science, studying an imperfect species, conducted by said imperfect species. But science has fail-safes to make up for human limitations, while the internet does not.

I encourage you to use this science. Read articles and books accessible through the library. And, most of all, be skeptical.