Scientific studies about climate change, more often than not, evoke a feeling of hopelessness and doom. In an era when even the existence of global warming is under scrutiny, one can’t help but feel anxiety levels begin to rise just like sea levels.

In a 2021 study that looked at responses from over 10,000 participants aged 16–25 years in ten countries, nearly 60% of respondents reported feeling that humanity is doomed.

This widespread sentiment, persistent especially amongst young people, has a name: eco-anxiety. Glenn Albrecht, a professor at the Murdoch University in Western Australia, originally coined the term in 2011 to describe a chronic fear of environmental doom.

It may be telling that a number of other related terms have cropped up in the past decade. Ecological grief defines the grief felt in response to experienced or anticipated losses in the natural world; solastalgia is the distress one might feel when they see environmental change in their own backyard; eco-angst is a feeling of despair at the fragile condition of the planet.

These many words and, often, conflicting definitions for each, illustrate just how difficult these feelings are to pin down. Anxiety, grief, nostalgia and angst tend to slip out of concrete definitions and take on an individual flavor.

The ways individuals have learned to cope with these feelings are, well, individual. Intensive therapy and pharmaceuticals may be one person’s solution. Sharing experiences with a community may work for someone else. For others, turning to the arts has been helpful.

Nilanjana Das, a graduate student at Oregon State University, studies fish. Specifically, focusing on the effects of warmer river temperatures in Oregon on the severity of infectious diseases in salmon and trout.

According to Das, many aquatic nasties — like parasites, bacteria, fungi and viruses — thrive and replicate quicker in warmer waters. They can weaken the immune system in fish and make them more susceptible to disease outbreaks, leading to high mortality rates in already-imperiled Pacific salmon populations.

“I often feel an overwhelming sense of urgency regarding the need for disease mitigation strategies to prevent further harm to vulnerable fish populations,” Das said in an email. “Art allows me to channel that urgency into something tangible — a way to share these concerns and, in doing so, find relief in knowing I have a way to raise awareness and inspire action.”

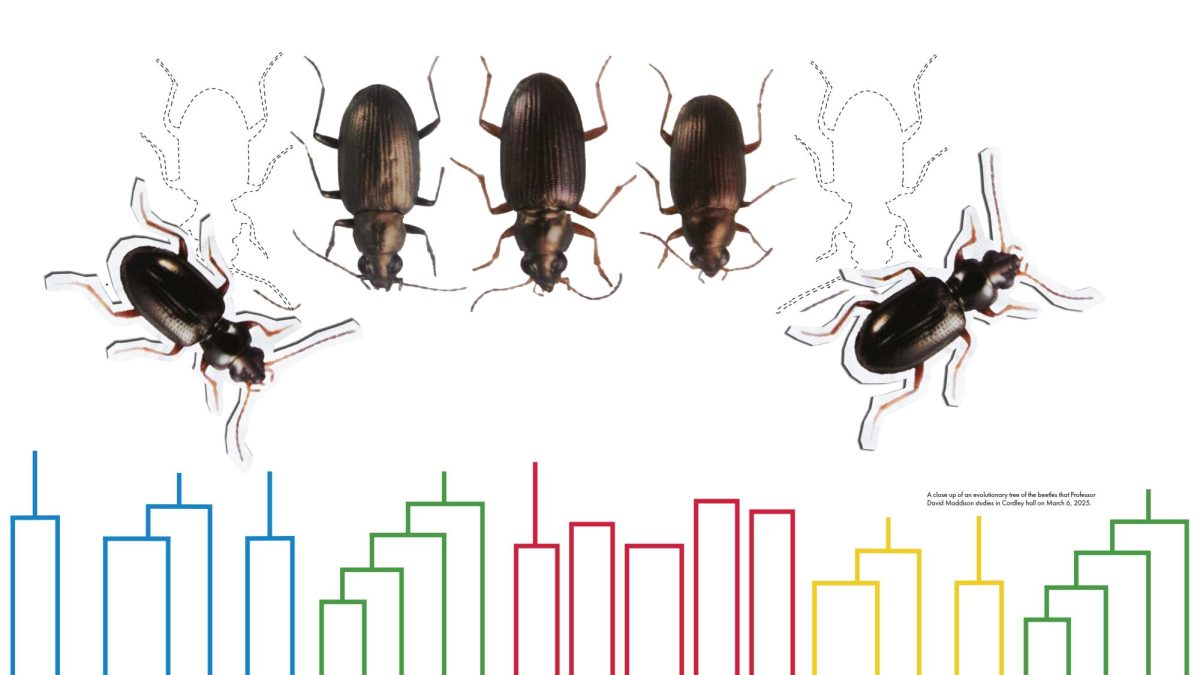

Das’ artistic inclinations go in many different directions, but her most recent installations at Hatfield Marine Science Center and in downtown Corvallis are sculptures. Using translucent wax paper and white basket twine, she creates huge depictions of the pathogens she studies.

Walking underneath them, a viewer may feel transported to an alien world — the pathogens certainly look a little alien. One of them, with bristles all around its circular body, Das colloquially calls the “scrubby brush.”

Of course, these are very earthly creatures. Oregon water teems with them and they affect other populations on large scales.

“I hope viewers will naturally ask, ‘What are they?’ and once they realize they’re infectious parasites, begin to reconsider the kind of environment and challenges that our regional fish populations are continuously navigating,” Das said.

In December 2024, Das’s art-science club, the Seminarium, attended a talk given by painter Robin Hextrum over Zoom.

Hextrum’s work has explored many avenues, but a large theme of hers has been climate change and ecological decline. During Hextrum’s first month of college, Hurricane Katrina hit.

“This enormous disaster happened just as I was starting to pay more attention to the larger world around me,” Hextrum said in an email. “I worked on a series of floodscapes to try to work through the constant news imagery of flooding that I saw around me.”

Hextrum said she sought to process the aftermath of natural disasters in a still and quiet way by painting a single object or animal floating in a “never-ending gray expanse of water.”

During her time in California and Colorado, Hextrum experienced a number of other natural disasters that caused widespread ecological damage, and emotional distress for her and her loved ones.

“Now there are terrible fires raging across southern California, and it feels apocalyptic to take it all in. I think I need to use art as an outlet to process all of this,” Hextrum said.

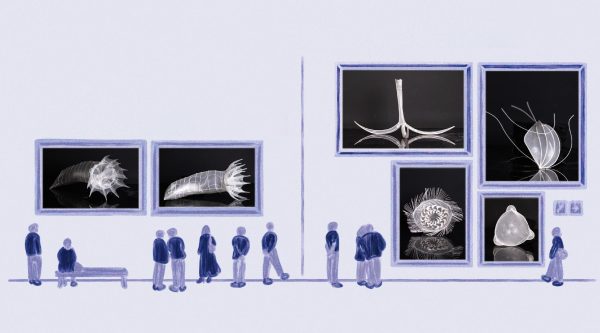

Hextrum’s recent work combines imagery of icebergs with flowers from 17th century Dutch still-life paintings. This old genre of paintings capture the beauty of flowers that were usually imported from global trade-routes — classically, tulips. According to Hextrum, this represents an era of trade, colonialism, market capitalism and consumption.

“Juxtaposing icebergs with imagery from traditional Dutch paintings asks us to examine how the historical relationship between humans and the environment has generated a legacy of a warming planet,” Hextrum said.

For Hextrum, art is a form of personal catharsis, but she also seeks to provide a space for reflection.

“I feel we are often in a state of terror, panic, or denial around this topic and I want to make a space where viewers can just stop and reflect. I want to give people the opportunity to contemplate their own anxieties,” Hextrum said.

In addition to this, both Das and Hextrum see art as a potent way to raise awareness and, possibly, provide a solution.

“I hope that offering them this moment also opens up some space to think constructively about what (the audience) might do every day to be part of the solution,” Hextrum said.

Das hopes to bring awareness, not only to large climate issues, but to the research she is passionate about — and that not many people may know about.

“It’s my hope that curiosity can then lead people to explore the efforts that are already being taken by scientists, natural resource managers and conservations to mitigate disease issues, and support them,” Das said.