Alysia Vrailas-Mortimer conducts research at Oregon State University on fruit-flies, trying to understand the genetic and environmental factors that contribute to aging and diseases related to aging, such as Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease and different muscular dystrophies.

When hearing about aging research most people will automatically assume it involves finding immortality but Vrailas-Mortimer thinks differently.

“I think one of the things — being an aging researcher — is that a lot of times people think about extending lifespan, but really what we want to do is extend healthspan,” Vrailas-Mortimer said.

There has been a heightened interest in the negative effects of aging. Vrailas-Mortimer believes this is due to the fact we are looking at ourselves more than ever before.

“We see our faces so much more than we used to because we’re on the screens, and we watch the videos, and we see ourselves on Zoom. … So I think we are tending to spend so much more time on what we look like than we ever used to before,” Vrailas-Mortimer said.

The main purpose of this research is to understand how our genes affect our health as we age.

“I would say with our research we also look at the role of our aging gene in diseases of aging. So trying to understand how genes promote lifespan and healthspan, what happens to them when we combine them with a mutation that causes a disease, and could these aging genes be good targets for the development of therapeutics for the treatment of these diseases of aging,” Vrailas-Mortimer said.

Getting accurate data can be difficult for any research team as external factors have a massive impact on our lives.

“We have the benefit of the flies. We control their environment for them. So whenever we set up an experiment, we have our control group and our experimental group and then they’re going to be experiencing everything together. They’re eating the same food, they’re getting the same temperature and humidity conditions and the same sleep schedules. And so the idea is we control as much of that environment as we can, so the only difference is whatever our treatment is,” Vrailas-Mortimer said.

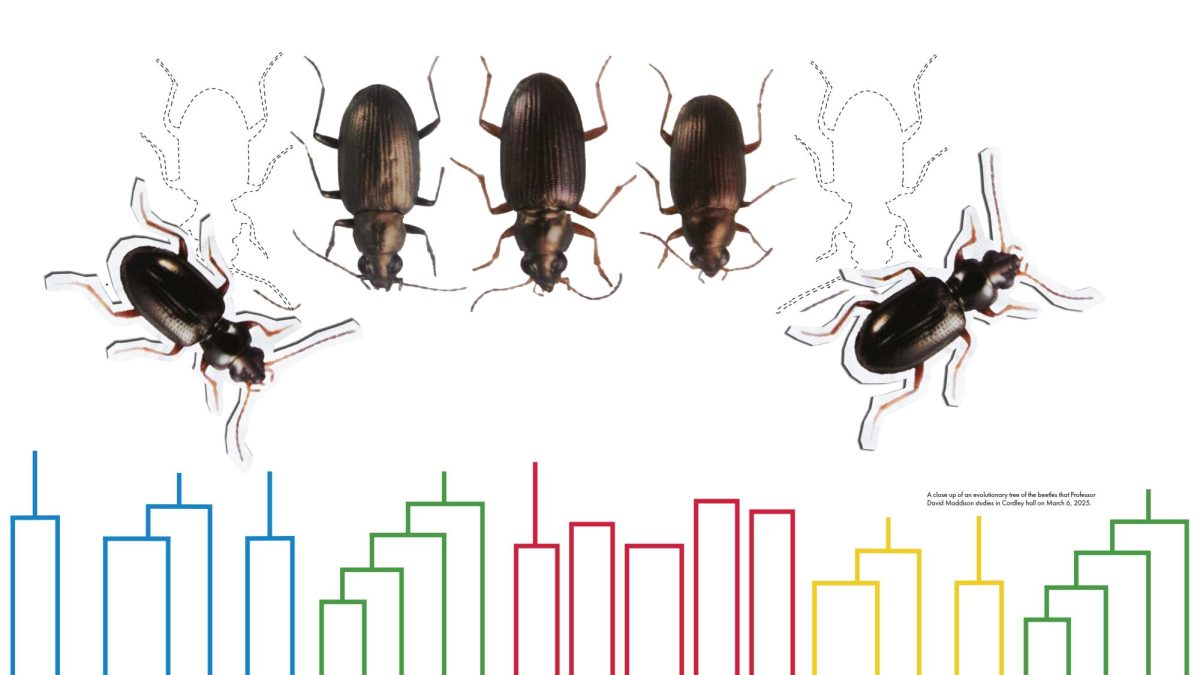

There are many different model systems to choose from to conduct this research. The flies were chosen because of many different reasons.

“We can model different diseases. So even if flies don’t have that disease gene, we can express a version of that gene in a fly and see how (it causes) a disease,” Vrailas-Mortimer said. “So we learn an awful lot. (Flies) are a lot simpler than us but it gets us to that basic understanding and then we can build on that with other mammalian models.”

One of Vrailas-Mortimer’s key findings is the p38 MAP kinase gene. “One of the most exciting things we found is (the p38 MAPK gene) that regulates aging,” Vrailas-Mortimer said. “It’s a stress response gene. So when we experience stress, … what it’s going to do is allow for our cells to be able to cope with that stress.”

The P38 gene has proven helpful in this research for many different reasons.

“We found that if we over-express this gene — so we have the flies make more than they normally would — … that extends their lifespan by 37%. So if we think about that for humans, our average lifespan is about 78 years. This would increase it to 107 years. So it is a really major increase in how long these animals are living. And they’re also healthier,” Vrailas-Mortimer said.

When the p38 MAPK gene was removed, the fruit-flies experienced a shorter lifespan and began having more locomotor defects. The flies were not able to climb or walk as well compared to a normal fly.

Aging comes with many downfalls that Vrailas-Mortimer is trying to improve.

Getting older also puts people at a higher risk for developing diseases. This is due to the fact that the different components of the cell start to wear out as we age and the ability for our cells to repair themselves decreases.

The human body is built to fight disease. Vrailas-Mortimer used Parkinson’s disease as an example where the dopaminergic neurons in a specific part of the brain become affected by the mutation slowly killing the neurons. But, the patient will not start to experience the common symptoms of the disease until 60-80% of the neurons have died.

The Linus Pauling lab where this research is done is an open concept lab, which is made to promote cooperation and encourage new ideas between researchers.

The flies that are used in the research are kept at room temperature and often held in incubators to make sure the control and experimental groups are kept at the same conditions. The flies also all eat a mixture of molasses, cornmeal, yeast and auger, which hardens the food and gives the flies a place to stand.

One piece of advice Vrailas-Mortimer left with in regards to aging is: “Just enjoy our lives, we never know when they are going to end.”