- Beavers Digest

- Beavers Digest / Culture

- Beavers Digest / Culture / Community

- Beavers Digest / Culture / Expression

- Beavers Digest / Culture / People

Quiet on set: How the writers’ strike impacts students & Guild members in Corvallis

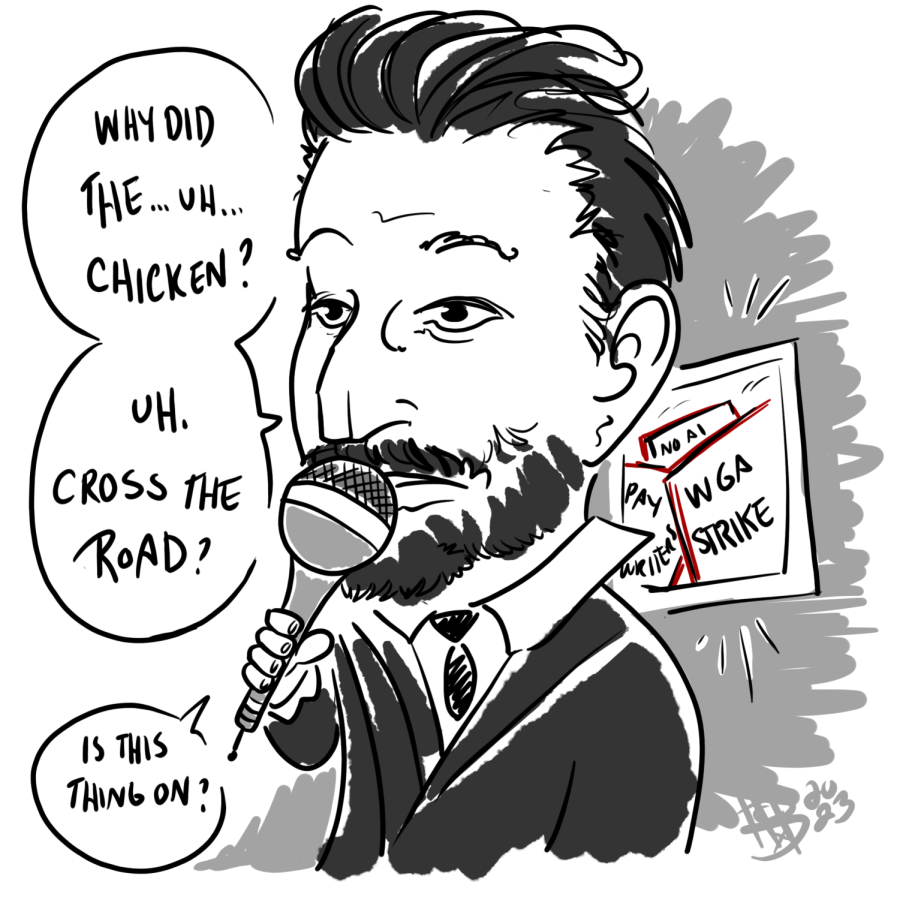

An illustration of a talk show host trying to make a joke while the Writer’s Guild protests continue in the background.

Thousands of Hollywood screenwriters replaced pencils with picket signs by going on strike for the first time in 15 years.

The Writers Guild of America, a labor union representing over 11,000 screenwriters in film and television, went on strike on Tuesday, May 2 after contract negotiations with the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers failed. Now, after two weeks, writers and filmmakers everywhere eagerly wait for the first move to be made toward a resolution.

Central demands from the WGA regard livable wages and job security with the rising use of artificial intelligence to generate film and TV scripts.

Rumors of a strike began circulating within the Guild this past winter after “big stumbling blocks in negotiations” took place, according to David Turkel, WGA union member and writing instructor at Oregon State University.

After playwriting for over 25 years and founding multiple theater companies, Turkel became a staff writer for the TV adaptation of the early 2008 film “Let the Right One In.” Turkel then joined the WGA after the series’ release in 2020.

Turkel explained how the structure of TV writing has changed over the years as shows have shifted from a standard 22-episode season model to a reduced eight to 10 episodes. This directly impacts screenwriters’ livelihoods as most are either paid per episode written or paid “scale,” which is the minimum amount to be paid for written work according to the WGA Series Compensation Guide on their website.

In addition to fair pay, the WGA also demands job security and guidelines as the usage of AI-generated scripts and content become more prominent across the job market.

“It’s a pressing question for everyone: What happens if you try to get AI to break a whole season?” Turkel proposed. “And then you hire less writers because the season’s broken – so, is that something (producers) would try to do? I’m sure they would, so that’s one of the things (the union) is gonna negotiate.”

Turkel also referenced a recent discussion with a colleague about the impact of the human experience in writing against the results of AI-generated scripts.

“If a human being … (reads) a bunch of influential texts, they’re gonna be looking for the thing that sparks them that’s new and different,” Turkel said. “Whereas AI is trying to create an amalgamation of what already exists. So, you have a natural thing that feels like AI is not gonna be capable of bringing to the game.”

As uncertainty for the future builds for current and prospective writers, OSU students shared mixed feelings on the outlook of the conflict.

Daniel Zahariev, OSU’s film club founder and president, expressed concern regarding the comparison of salaries between studio executives and screenwriters: “It’s a common saying in the industry that a film – or any post-produced TV, really – is made three times: once when written, once when filmed and once when edited. Screenwriters, as a third of that, ought to be paid a fair and livable amount for their work.”

Zahariev also shared a sense of fear at the idea of going into the film industry after observing the treatment of screenwriters. “However, seeing a labor union empowered to fulfill its purpose and how the public at large has responded so positively – I suppose it makes me optimistic,” Zahariev added.

On the other hand, the situation makes some feel unsteady about the future of writing as a profession.

Miranda Lenore, a third-year theater and creative writing major at OSU, stated in a survey, “It’ll be hard to build a career I’m proud of if the only things that matter are profits,” and further expressed how this fuels discouragement towards creating in the film industry in general.

“That’s not what makes the industry good or worthwhile,” Lenore said. “That’s not why anyone is compelled to make art.”

“The only thing (the strike) makes me realize is that writing is a profession just like any other,” Max Freedman, a second-year sociology major, added. “Being a writer doesn’t make you immune to people trying to take advantage of your effort, and sometimes that means you need to push back.”

While noting the potential risk of finding future jobs and the copious effort in organizing a strike, students who responded to the survey overwhelmingly agreed that the strike is necessary for changes to working conditions in the film industry to be made.

Turkel also shared an optimistic outlook by mentioning that, while the WGA is the union actively on strike, union representatives are also backed by other Hollywood labor unions, including the Screen Actor’s Guild and the Director’s Guild, providing a “strong coalition.”

“(No decision) is gonna get made without some positive development and I think that all points toward the direction of a beneficial resolution to the whole conflict,” Turkel added.

As the strike continues, writers on the picket lines and studio producers prepare for a lasting standoff, and writers, both on and off the OSU campus, watch carefully for what the future of film brings.