Genocide romanticized: Professor says Thanksgiving traditions ignore dark history

By Duane Knapp, OMN Photographer

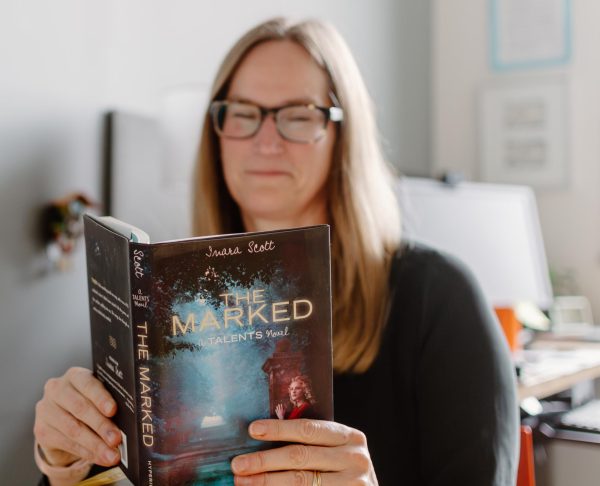

Director of the School of Culture, Language and Society, Susan Bernardin sits in her office at Oregon State University in Corvallis, Ore. Stories like the one we hear about Thanksgiving, the Oregon trail or Pocahontas are wish-fullfillment narratives created to cover up the brutal reality of how this country’s birth grew out of mass genocide and slaughter, explained Bernardin.

November 22, 2022

Thanksgiving is a complex celebration. It is a time when many of us get together with the ones we are closest to and give thanks for what we have. However, the history behind the holiday is not so joyful.

The pleasant story that has been broadcasted of the Wampanoag tribe and the early settlers working together in harmony during harvest to share a big meal of gratitude is the whitewashed version of history. Yet, regardless of whether there is any truth to the story, “we want to ask ourselves why are these stories so powerful and why they are so hard to reckon with,” according to Susan Bernardin, director of the School of Language, Culture and Society and professor of Indigenous studies at Oregon State University.

These stories are “reimagining genocide and removal into an interracial national romance,” Bernardin said.

Instead of focusing on the facts behind the happy story we have been told since childhood, Bernardin suggested we focus on how these kinds of stories have covered up the mass genocide that occurred in this country. The histories behind these stories are best seen through the point of view and stories of the Indigenous tribes that are still here today.

Unlike many other countries, Bernardin said “in the United States, we have not had any national reckoning with our genocidal histories.”

Stories like the one we hear about Thanksgiving, the Oregon trail or Pocahontas are wish-fullfillment narratives created to cover up the brutal reality of how this country’s birth grew out of mass genocide and slaughter, explained Bernardin.

And today Indigenous communities are still facing unjust realities.

Bernardin stressed the significance of how the Supreme Court is currently looking to possibly overturn the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, which says that when custody disputes of Indigenous children are heard at the state court, the judge should try and place the children with an extended family member, another member of the tribe or other native families.

According to studies conducted by the Association on American Indian Affairs, before this was enacted, 25-35% of all Indigenous children were separated from their families in 1969 and 1974.

The possibility of this act being overturned is a “grave threat to tribal sovereignty” Bernardin said.

In order to move forward and heal as a country we first need to understand the realities of our origin.

“Truth-telling is a prerequisite to reconciliation,” said Bernardin.

So this Thanksgiving, “a bigger takeaway is, what does it mean to have gratitude?” Bernardin said.

Bernardin brought up how the pandemic made it very clear how important being in community is and sharing food with those closest to you can be a powerful tradition. She said we should think more about how Thanksgiving could be an opportunity for us to actually come together, work towards understanding each other better,and then start to reconcile with our past and present.

A good place to start the unlearning process is by asking questions and learning the history of the land you live on, Bernardin said. She recommended:

- Visit Tribal Nations websites

- Support Indigenous-owned bookstore

- Listen to the All My Relations podcast

- Boost Indigenous folks on TikTok

- Native American Calling

Or take some classes in the newly-added Indigenous Studies minor here at OSU starting with ES 260. The Indigenous Studies program here is an interdisciplinary field that not only reckons with dark histories but also teaches about Indigenous knowledge systems and the vibrancy of their communities.